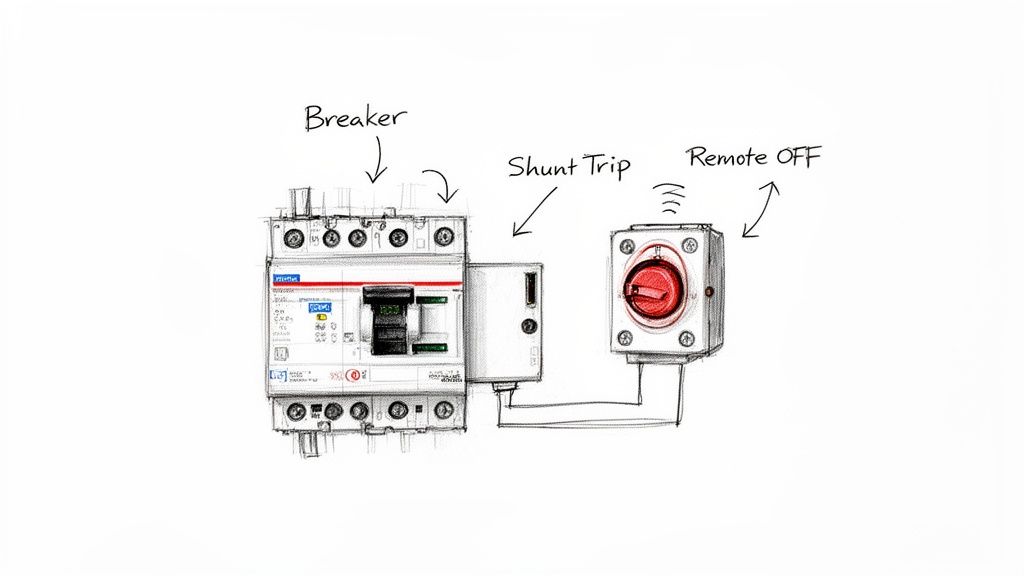

Think of a standard circuit breaker. It's a fantastic, self-sufficient device that sits there quietly, waiting to spring into action when it detects an overload or short circuit. But what if you need to tell it to turn off, right now, from the other side of the factory? That’s where a shunt trip comes in.

A shunt trip is an accessory you add to a circuit breaker that essentially gives it a remote "off" switch. It allows an electrical signal—not an overload—to trip the breaker intentionally. This isn't about routine circuit protection; it's about providing a controlled, immediate shutdown for critical safety or operational reasons.

Defining the Role of a Shunt Trip Device

At its heart, a shunt trip decouples the reason for a shutdown from the breaker's physical location. A normal breaker is purely reactive and local; it only cares about the current flowing through it. The shunt trip introduces a powerful new capability: remote, commanded tripping.

This function isn't designed to save wires from getting hot. It's designed to protect people and machinery. Imagine it as a tiny, clever messenger that connects a big, powerful circuit breaker to a simple, accessible control signal. A push button, a relay from a fire alarm panel, or a PLC output can send a small pulse of voltage that instantly kills power to a massive piece of equipment.

Its Primary Purpose in a System

The whole point of a shunt trip is to shut things down based on an external command, whether from a person or another system. It answers the critical question, "How do we safely kill power to that machine from over here, right now?"

This is non-negotiable in countless industrial and commercial scenarios. Its most common jobs include:

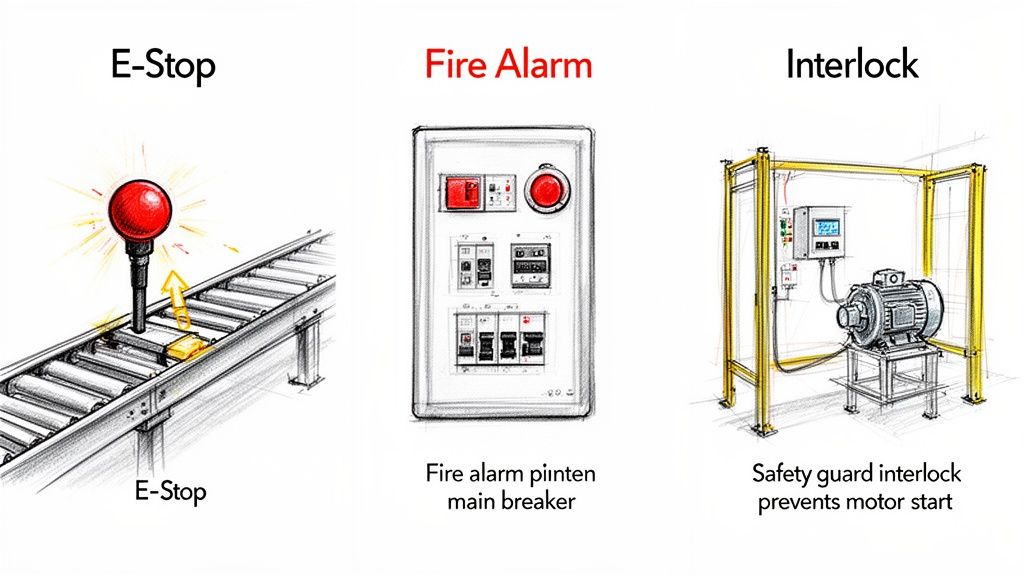

- Emergency Stop (E-Stop) Circuits: This is the classic application. An operator hits a big red button, and the shunt trip instantly de-energizes the connected machinery.

- Fire Safety Integration: In an emergency, a fire alarm system can signal the shunt trip to cut power to high-risk equipment like HVAC fans (to stop smoke from spreading) or elevators.

- Process Control Interlocks: It can prevent a machine from running under unsafe conditions. For example, if a safety guard on a conveyor is opened, a sensor can signal the shunt trip to stop the motor immediately.

A shunt trip fundamentally changes a circuit breaker from a passive, automatic protection device into an active component of a larger safety or control system. It provides a reliable method for controlled, remote de-energization.

How It Differs from Other Breaker Functions

It's easy to get a shunt trip mixed up with other trip mechanisms inside a breaker, but they operate on completely different principles.

A standard thermal-magnetic trip is the breaker's built-in bodyguard, automatically reacting to overloads and short circuits. An undervoltage release (UVR) is another animal entirely—it trips the breaker when its control voltage is lost, which is great for preventing machines from unexpectedly restarting after a power outage.

A shunt trip is the exact opposite of a UVR. It trips the breaker when voltage is applied to its coil. Understanding this difference is absolutely critical when designing safe and reliable control circuits.

Shunt Trip vs Other Circuit Breaker Trip Functions

This table breaks down the key differences at a glance.

| Trip Mechanism | Activation Trigger | Primary Purpose | Operation Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shunt Trip | Voltage is applied to a coil. | Intentional, remote shutdown. | Commanded |

| Thermal-Magnetic | Overcurrent or short circuit is detected. | Automatic circuit/wire protection. | Automatic |

| Undervoltage Release | Control voltage is lost. | Prevent restart after power failure. | Automatic |

Each mechanism serves a distinct purpose. While a thermal-magnetic trip handles electrical faults, the shunt trip and undervoltage release are all about integrating the breaker into a broader control and safety strategy.

How a Shunt Trip Actually Works

To really get what a shunt trip does, picture a mousetrap. Your circuit breaker is loaded with powerful springs held in tension, just itching to snap the electrical contacts open. The shunt trip is basically the remote trigger for that trap.

When you hit an emergency stop button or another control device sends a signal, a specific voltage energizes a tiny solenoid coil inside the shunt trip accessory. This isn't high-tech magic; it's basic physics. The coil instantly creates a magnetic field, turning a small piece of metal into a temporary, but surprisingly strong, electromagnet.

That magnetic force is the whole secret. It shoots a small metal pin (the plunger) forward with a sharp kick. This plunger has one job and one job only: to mechanically smack the breaker's internal trip bar. This is the very same mechanism that a thermal or magnetic overload would trigger during a fault.

As soon as that trip bar is nudged, the breaker's main operating mechanism is released. All the energy stored in those powerful springs is unleashed, violently forcing the electrical contacts apart. This instantly breaks the circuit and kills the power.

The Electromechanical Handshake

This whole sequence is a classic electromechanical process. You have an electrical signal creating a magnetic field, which in turn creates physical motion to trip the breaker. It’s brutally simple, incredibly fast, and very reliable.

The beauty of the shunt trip is its direct-acting design. There are no delicate electronics or complicated logic inside the accessory itself. It's just: voltage in, plunger out. This robust nature is exactly why shunt trips are trusted for critical safety functions where you absolutely cannot afford a failure.

Of course, to fully appreciate how this accessory works, it helps to have a good handle on how modern circuit breakers operate in the first place, since the shunt trip is just piggybacking on the breaker's built-in trip system.

Key Components in Action

Let’s quickly break down the parts that make this happen. Understanding these pieces is key for any technician troubleshooting a control panel or an engineer trying to specify the right part.

- Solenoid Coil: This is the heart of the device. It’s wound to respond to a specific control voltage—like 24V DC, 120V AC, or 240V AC. Getting this wrong is a common mistake; sending 120V AC to a 24V DC coil will fry it instantly, while sending too little voltage means it won't have the oomph to work at all.

- Plunger/Actuator: This is the muscle. It’s the little pin that the magnetic field launches forward. Its movement has to be quick and forceful enough to reliably hit the trip bar every single time.

- Trip Bar Interface: Think of this as the point of impact. It’s the specific mechanical spot where the shunt trip’s plunger makes contact with the circuit breaker's internal trip mechanism, transferring the force needed to open the circuit.

From the instant voltage hits that coil to the breaker contacts flying open, the entire event is over in less than 50 milliseconds. That kind of speed is non-negotiable in emergency shutdown scenarios where every fraction of a second is critical to preventing equipment damage or, more importantly, protecting people.

Essential Wiring and Integration Schematics

This is where the rubber meets the road. Getting a shunt trip properly wired into a control circuit is the difference between a reliable safety device and a disaster waiting to happen. The goal is simple: deliver a quick pulse of control voltage to that coil at the exact moment it's needed—and absolutely never by accident.

At its heart, the wiring isn't complicated. You've got two terminals on the shunt trip coil. One side gets tied to a control power source, while the other runs to your control device, like an emergency stop button or a PLC output. When that device closes the circuit, juice flows through the coil, and click—the breaker trips. Easy concept, but the devil is in the details that keep it safe and reliable.

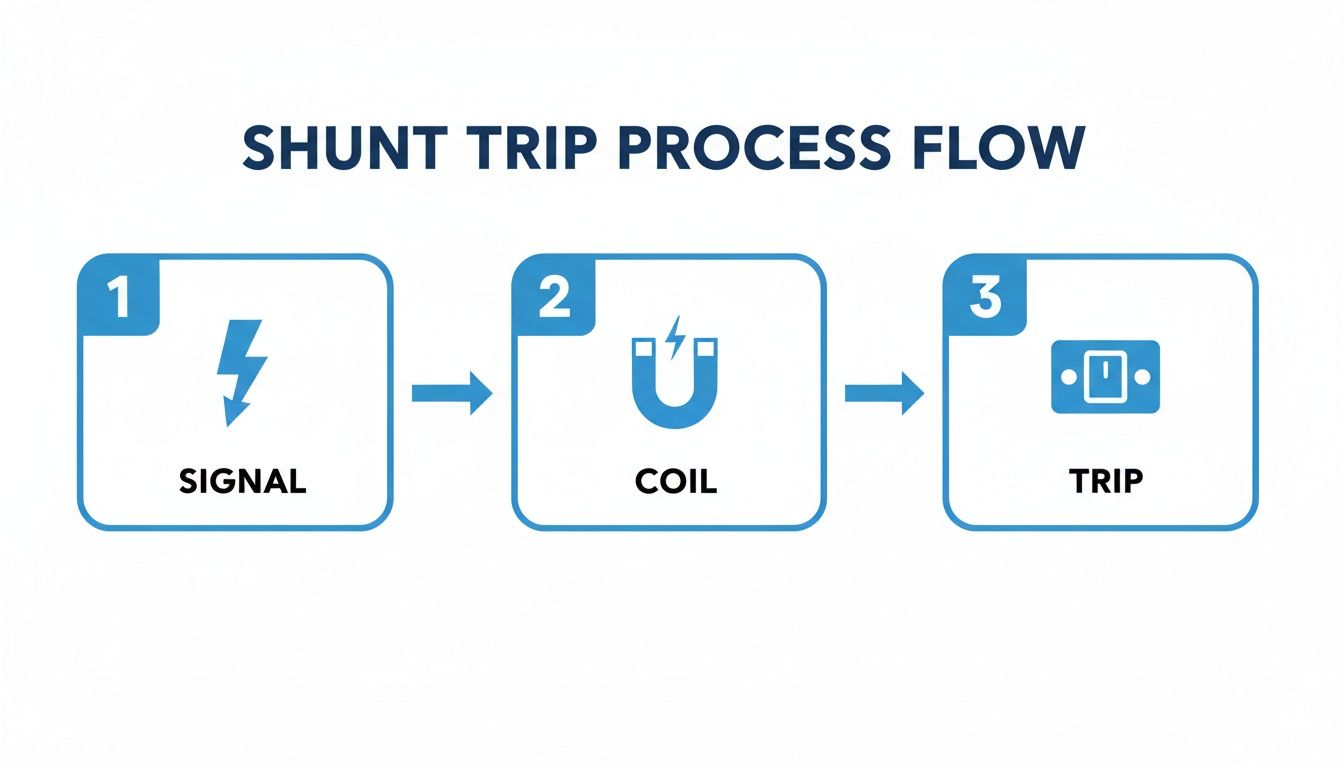

This flow diagram breaks down the dead-simple, three-step chain of events that happens once a signal is sent.

As you can see, it's a direct cause-and-effect sequence: an electrical signal fires up the coil, which triggers a mechanical action to open the circuit.

Wiring for an Emergency Stop Circuit

The classic big red mushroom-head Emergency Stop (E-Stop) button is probably the most common partner for a shunt trip. The logic couldn't be simpler: smash the button, kill the power. To make this work reliably, the E-Stop contact you use has to be Normally Open (N.O.).

Here’s how it plays out:

- Standby: The E-Stop is untouched, so its N.O. contact is open. No voltage can get to the shunt trip coil, and the breaker stays on, business as usual.

- Action: Someone hits the E-Stop. The button closes that N.O. contact, instantly completing the control circuit.

- Trip: Voltage zips through the closed contact, energizes the shunt trip coil, and the breaker trips open, shutting down the main circuit.

One critical detail here is the control power source. Per standards like UL 508A, this control circuit needs its own dedicated fuse or breaker. This keeps the control wiring protected and ensures a short in the E-Stop circuit doesn't create an even bigger headache. If you're a visual learner, checking out a wiring diagram for a shunt trip breaker can really help connect these dots.

The big takeaway? The control circuit must be wired to apply voltage only when a shutdown is commanded. Using a Normally Open contact prevents a broken wire or loss of control power from nuisance-tripping the breaker. It also means your control power source better be rock-solid when you actually need it.

Integration with PLCs and Automated Systems

In the world of automated safety, shunt trips are indispensable. They're the muscle behind the brains of a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC). Think about a massive motor that has to shut down now if a bearing gets too hot or a pressure sensor screams danger.

Here, a digital output from the PLC takes the place of the E-Stop button.

- The PLC keeps a constant watch on sensors monitoring things like temperature, pressure, or position.

- If any value strays outside the safe zone, the PLC's programming logic flips a specific digital output from OFF to ON.

- That output sends voltage straight to the shunt trip coil, instantly killing power to the motor or machine.

This creates a high-speed, automated shutdown that doesn't wait for a human to react. The control power for this kind of critical circuit has to be bulletproof. That's why it's often backed up by an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS), ensuring the PLC can trip the breaker even if the main facility power is flickering. This isn't just good practice; it's a common requirement under the NEC (National Electrical Code) for emergency systems where safety functions can't be left to chance.

Key Applications in Industrial Safety and Control

Once you get past the technical diagrams and mechanics, the true power of a shunt trip shines in its real-world applications. This isn't just an optional accessory; it's a linchpin for modern industrial safety and control systems. Its ability to act on a remote command makes it the perfect tool for protecting people, safeguarding expensive equipment, and keeping operations running smoothly.

Think of it as the ultimate "off" switch. Whether it's for an emergency shutdown or an automated process, the shunt trip offers a reliable and instant way to de-energize a circuit. This simple but powerful function is what makes it so indispensable across so many industries.

Emergency Shutdown Systems

The most classic role for a shunt trip is inside an Emergency Stop (E-Stop) circuit. In any factory or processing plant, operators need a foolproof way to kill power to machinery in a crisis. The industry standard is simple: a big, red, easy-to-smack E-Stop button wired to a shunt trip on the main breaker or motor starter.

When an operator hits that button, the control circuit energizes the shunt trip’s coil, which instantly trips the breaker. It’s a direct, hardwired shutdown that’s far more reliable than software or complex logic that could fail when you need it most. It creates a definitive mechanical break in the power, guaranteeing the machine stops dead.

Fire Safety and Alarm Integration

During a fire, live electrical systems can make a bad situation much worse, feeding the flames or creating shock hazards for first responders. Shunt trips are a critical part of mitigating that risk. Modern fire alarm control panels (FACPs) are almost always built with auxiliary relay outputs that activate the moment an alarm is triggered.

Those relays can be wired directly to shunt trip coils on main distribution panels or circuits feeding high-risk equipment. When the fire alarm goes off, it automatically sends a signal to trip those breakers. This de-energizes non-essential equipment and shuts down HVAC systems to prevent smoke from circulating. It's an automated response that helps contain the emergency and create a safer environment for firefighters.

A shunt trip circuit breaker is a specialized safety device designed for remote power disconnection via an external signal. The global market for these devices was valued at USD 1.1 billion and is projected to reach USD 2.2 billion by 2033, growing at a rate of 8.5% annually. This growth highlights the increasing demand for advanced electrical safety across all industries. To understand more about this trend, you can discover more insights about the shunt trip market on cncele.com.

Process Interlocking and Equipment Protection

Beyond just protecting people, shunt trips are vital for protecting the machinery itself through process interlocking. This just means creating a control circuit that stops equipment from running under unsafe conditions. A perfect example is a safety guard on a machine with dangerous moving parts.

A sensor on that guard can be wired into the shunt trip's control circuit. If an operator opens the guard while the machine is running, the sensor signals the shunt trip to immediately kill power to the motor. This simple interlock prevents injuries and stops equipment from being damaged by improper use. Shunt trips are indispensable in various sectors; for instance, they are a critical safety component in advanced industrial automation solutions. This kind of basic interlock is a foundational piece of machine safety design, ensuring that safety rules are physically enforced, not just suggested.

Choosing the Right Shunt Trip for Your Application

Picking the right shunt trip isn’t just about finding a part that fits inside the breaker. It’s a critical decision that has a direct impact on the safety and reliability of your entire system. For any engineer, project manager, or technician on the floor, getting this specification right from the start ensures this little safety device does its job when it matters most.

Getting it wrong leads to costly rework, frustrating nuisance trips, and—worst of all—a safety system that might not work at all.

Matching Voltage and Breaker Compatibility

The first and most common pitfall is the coil voltage. It's an easy mistake to assume the shunt trip’s voltage should match the main circuit voltage. That's almost never the case.

The shunt trip coil must be matched to the control circuit voltage. So, even if your breaker is handling 480V AC, the control circuit powering the shunt trip is often a much safer, lower voltage like 24V DC from a PLC or 120V AC from a control transformer.

Your control scheme is what really dictates the coil you need. If a PLC is doing the thinking, you're likely looking for a 24V DC coil. If it's a simpler hardwired circuit tied to standard facility power, a 120V AC coil is more common. You have to specify both the voltage and the type—AC or DC. They are absolutely not interchangeable. Powering a DC coil with AC voltage (or the other way around) is a surefire way to let the magic smoke out.

Beyond voltage, compatibility is completely non-negotiable.

- Model-Specific Design: A shunt trip is not a generic, off-the-shelf part. It's a purpose-built accessory designed by the manufacturer for a specific series or frame size of circuit breaker.

- Physical Fitment: The device has to physically connect with the breaker's internal trip bar. A shunt trip made for an ABB breaker, for example, simply won't fit or function in a Schneider Electric breaker. It's a lock-and-key situation.

- UL Listing: To keep the UL listing of your panel or assembly intact, you must use accessories that are specifically listed and approved for that exact breaker model. No substitutions.

If you're working with a specific product line, digging into the manufacturer's documentation is essential. For more on this, our guide on the ABB circuit breaker lineup can offer some deeper, brand-specific insights.

Understanding Duty Cycle and Inrush Current

Another crucial detail that often gets missed is the duty cycle. Most standard shunt trip coils are built for intermittent duty only. They’re designed to get a quick pulse of voltage—just long enough to unlatch the breaker, which is usually less than a second.

Energizing a standard intermittent-duty coil continuously is a recipe for failure. The coil will quickly overheat, burn out, and become a useless piece of melted plastic. If your application needs a continuous signal, you have to source a special (and often more expensive) continuous-duty rated shunt trip.

Finally, think about the inrush current. The moment it’s energized, that little solenoid coil draws a much higher current than its steady-state rating. Your control power supply, and any relays in between, must be beefy enough to handle that momentary surge without a voltage dip. If the voltage sags, the coil might not get enough juice to decisively actuate the trip mechanism, leaving you with an unreliable safety function. Getting this right ensures your system performs robustly every single time it's called on.

Troubleshooting Common Shunt Trip Issues

Even the most well-designed safety systems have their off days. When a shunt trip circuit decides to act up, it can bring operations to a grinding halt and cause major headaches for everyone involved. For the maintenance crews and technicians in the field, knowing how to quickly track down the source of the problem is a vital skill that keeps the line moving and people safe.

This is your hands-on guide to diagnosing and fixing the most common shunt trip failures. We’ll break down each scenario into a simple problem, cause, and solution format—no guesswork, just a clear path to getting things running again.

Problem: The Breaker Trips the Second You Try to Close It

It’s one of the most frustrating things to see: you go to reset a breaker, and it trips again instantly. This immediate "trip-on-close" condition is a classic sign that an active signal is being fed to the shunt trip coil, physically preventing the breaker from latching.

Before you start tearing into the breaker itself, take a step back and look at the control circuit. The real culprit is almost always an external device stuck in the "trip" position.

Common Causes and Solutions:

- A Stuck E-Stop Button: This is the number one cause, hands down. An Emergency Stop button was pressed but never properly reset. You need to physically walk the line and inspect every E-Stop station, making sure they are all pulled out or twisted back into their normal position.

- A Welded Control Relay: The relay that sends the trip signal is supposed to be normally open, but its contacts can sometimes weld themselves shut. This creates a continuous trip signal. Isolate that relay and use a meter to check its contacts for continuity.

- Mismatched Wiring: If the panel is new or someone has been working on it recently, the wiring might be the problem. A circuit wired through a normally closed (N.C.) contact instead of a normally open (N.O.) one will send a constant trip signal by default.

Remember, a shunt trip is just doing its job—acting on a signal. If the breaker refuses to close, it’s usually because it's getting a perfectly valid command to stay open. The problem is almost always in the signal source, not the breaker.

Problem: The Shunt Trip Won't Operate at All

Now for the opposite problem, which is arguably far more dangerous: you hit the E-Stop, and nothing happens. This means there’s a break somewhere in the chain of command between your control switch and the shunt trip mechanism. When your stop button fails to stop, you have to find the point of failure, and fast.

This kind of issue almost always comes down to a loss of power or a simple break in the circuit's continuity. The best place to start is with the fundamentals.

Key Areas to Investigate:

- No Control Power: Is the control circuit even hot? Check for a blown fuse or a small control circuit breaker that may have tripped. The coil can’t activate if it has no power to begin with.

- A Burned-Out Coil: Standard, intermittent-duty coils aren't designed to stay energized for long. If a signal was held on it for too long, the coil may have simply burned out. You can test this by checking its resistance with a multimeter—an open-loop reading (OL) means the coil is shot.

- Loose or Broken Wires: Vibration is the enemy of tight connections. Over time, wires can work themselves loose from terminals. Do a thorough visual inspection of all the wiring, from the E-Stop all the way to the shunt trip terminals on the breaker, and make sure every connection is solid.

Of course, many factors can make a circuit breaker trip. For a broader overview, you can learn more about what can cause a breaker to trip in our related guide. A methodical troubleshooting process, starting with the simplest and most likely causes, will help you solve these issues and get your equipment back online safely.

Common Questions We Hear About Shunt Trips

Even after you get the hang of what a shunt trip does, a few practical questions always pop up. Let's tackle the most common ones to clear up any confusion and make sure your designs are safe and solid.

Does a Shunt Trip Need to Be Reset After It Operates?

Yes, it absolutely does. When a shunt trip fires, it physically kicks the circuit breaker handle into the "tripped" position. You'll usually find it sitting halfway between ON and OFF.

You can't just shove it back to ON. It's a two-step process:

- First, push the handle all the way to the OFF position. This is the crucial step that resets the internal trip mechanism.

- Then, you can flip the handle back to the ON position to close the circuit again.

And don't forget the most important part: whatever triggered the trip in the first place has to be resolved. If an emergency stop button was pressed, it has to be released before that breaker will let you turn it back on.

Can a Shunt Trip Coil Be Left Energized Continuously?

In most cases, definitely not. The standard shunt trip coils you'll find in the field are designed for intermittent duty. Think of them as sprinters, not marathon runners. They're built for a very brief jolt of voltage—just enough to do their job, which usually takes less than a second.

Leaving continuous power on a standard shunt trip coil is a recipe for disaster. It will quickly overheat, melt its internal windings, and destroy itself. If your control scheme really needs a continuous signal, you have to track down a special continuous-duty rated shunt trip, which isn't nearly as common.

What Is the Difference Between a Shunt Trip and an Undervoltage Release?

This is probably the biggest point of confusion, but it's pretty simple when you boil it down. They do opposite things.

- A Shunt Trip needs voltage applied to its coil to trip the breaker. It’s an active command, like someone yelling "shut it down now!" This is what you use for things like an E-Stop button.

- An Undervoltage Release (UVR) needs voltage to be constantly present just to keep the breaker closed. If that voltage disappears—say, during a power outage—it automatically trips. UVRs are perfect for preventing machines from suddenly restarting when the power comes back on.

So, a shunt trip acts on the presence of a signal, while a UVR acts on the absence of one. Both are critical safety devices, but they solve completely different problems.

At E & I Sales, we work with components like shunt trips every single day, integrating them into robust, UL-listed control panels and motor control centers. If you need expert guidance on your next project, check out our system integration services.